Was the art world taken in by a true life version of the Emperor's new clothes?

We find ourselves staring back at an array of vacuous, albeit infamous, constructions parading as serious works of art and wonder how we ever fell for it at all. Is Damien Hirst, for example, truly even an artist at all?

Simply signing one's name on someone else's creation surely cannot constitute creating art? Yet, if we were to value his work solely in monetary value, Hirst could be considered one of the most successful artists whoever lived, his peers unrivaled in headlines and profits too.

Their predecessor, Andy Warhol, would no doubt have been proud of such a charade too. Peddling the illusion that art can be found in the humdrum world of mass-produced, easily replicable banality, Warhol was a figure who delighted in vacuity and kitsch rather than anything as troubling as nuance, meaning or emotion.

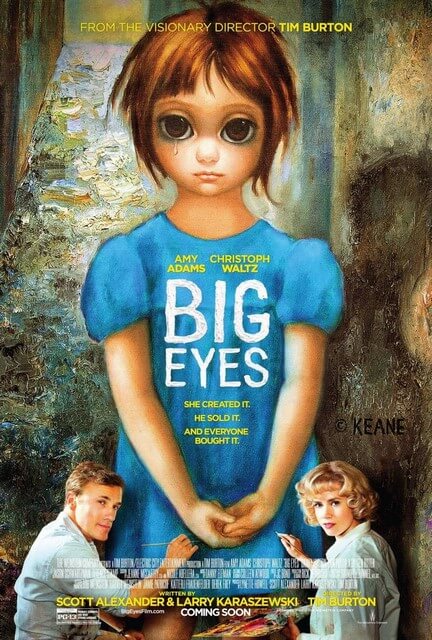

Tim Burton's latest movie, Big Eyes , begins with a quote from the American artist extolling the virtues of the mass-produced portraits of fragile waifs from which the film draws its name - if they were popular, Warhol stated, they had to be good art too, right? In his mind, popularity is a better gauge of quality than actual quality itself - a perverse view no doubt shared by businessmen and accountants across the globe, rather than artists who dedicate themselves to furthering their craft and chasing the sublime.

In Burton's latest feature, we meet the man who claims to have created the Big Eyes iconography - a charming, self-publicist called Walter Keane (Christoph Waltz). As adept at getting his name in the gossip columns as he seemingly is with a paint-brush, we learn that the "Keane" empire is built upon a tower of lies.

The true author of the paintings is indeed a "Keane", but not as the public understands; the meek Margaret (Amy Adams) spends her days behind easels creating the eerie images whilst her show-man husband drums up publicity and takes credit for the work. The situation isn't entirely dissimilar to Damien Hirst's deployment of anonymous workers to create art for him whilst the YBA "sells" them with his personality, adding fiscal value to the creations by lending them his name.

As the Keane empire grows and grows, Walter looks to further increase his family's income by making cheap, mass-produced posters of the Big Eyes paintings; they are placed for sale in hardware stores and gas stations, lined up in aisles next to the rows of similarly mass produced tins of soup of which Andy Warhol was so fond. For a man as concerned with fame and fortune as Walter Keane, the paintings have found their rightful place. For the art's true creator, his suffering and bullied wife Margaret, seeing her work exploited like this is a daily trouble for her. But what choice does she have but to go along with the scheme?

Unusually for an American movie, the hero of the hour is an art critic - one of the few people who can see through the baloney being peddled and one of the few people willing to call a spade a spade. This is as unusual in cinema as it is in real life and acts as a magnificent reminder that the truth is one of the most powerful tools in the universe when utilised correctly. When John Canaday (Terence Stamp) reveals that, perhaps, the Emperor is simply naked, the critic sets in motion a series of events which untangle the web of lies tightly wound by the Keanes throughout the years.

How can Walter Keane get the public to look at the Emperor with adoration again? Does Margaret even want this?

Big Eyes, an entertaining and engrossing movie, has the potential to mark something of a turning point in the career of Tim Burton who clearly saw a lot of parallels in the film's script and the latter stages of his own career.

As Walter Keane, upset with his fading fortunes, admonishes his wife for not delivering work which can easily be sold to the public, he scolds her, screeching the accusation she replaced the "sentimental with kitsch!"

In recent years, Burton himself has shied away from sculpting idiosyncratic, albeit deeply personal work, such as Edward Scissorhands and Big Fish, to create made-to-order rent-a-kook studio fare (such as Alice in Wonderland and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory). As such, this line of dialogue could easily act as a barbed critique of Burton who has been more than happy lately to put his name on mass-produced tat of little artistic value; that these films are amongst the most popular of Burton's career is a sad footnote but one which would no doubt please the Andy Warhols and Damien Hirsts of the world.

In Big Eyes, Burton self-reflexively addresses much of the criticism flung his way by imbibing the film with empathy and heart often missing in his cynically populist "studio" movies. He tells the tale of real people, and shows real courage in doing so - Burton allows Adams (as a broken Southern belle) and Waltz (as a conniving sociopath) to shine in their roles, allowing real substance to form the backdrop of his movie rather than relying on over-stylised aesthetics to superficially cloak vast expanses of emotionally emptiness. For the first time in a long time, this is a Tim Burton movie about people, their thoughts, feelings and fears - and, although it will certainly not make as much at the box office as Alice, is all the more richer for it.

Burton uses the world as seen through eyes of Margaret Keane to allow us to peer into the deeply personal worldview of Tim Burton; the eyes, after all, offer a window to the soul. And judging by Big Eyes, the director has an inordinate amount more soul than he has been showing of late. This is the first time in a long time that seeing the name "Tim Burton" upon a film has signified a true credit to the author of a movie, rather than simply being used as a branding tool.

This is Tim Burton not as Andy Warhol, Damien Hirst or Walter Keane but, more pleasingly, as Margaret Keane.

No comments

Post a Comment