Gaining access to the hermit kingdom, one of the most secretive and misunderstood nations on the earth, is something of a rarity, a coup - the country is tyrannical in its censorship and outsider views are entirely unwelcome.

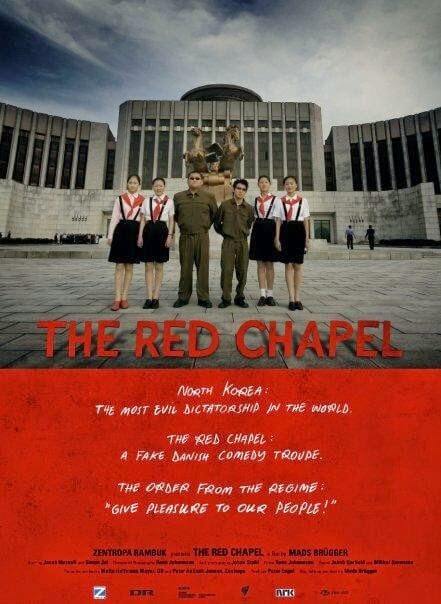

So, directly appealing to the DPRK's ego, the Danish director pitches a cultural exchange - a two-man theatre troupe will accompany him on his visit to showcase European performance arts to North Koreans. More than this, however, Brugger's colleagues were in fact adopted from South Korea as babies - to return to their land of origin but to choose the North over their capitalist neighbours could be seen as a great piece of propaganda for the communist country.

Their application to attend is accepted.

The Red Chapel is a peculiar film, not simply for the setting, but as much for Bruggen's bizarre insistence to make himself the star of the show. The documentary seems to have been created, primarily, to show Bruggen in North Korea rather than to show North Korea itself.

At one point, Bruggen decides to make a semi-political rant at his confused tour guides - they are as perplexed as we are, trying to understand his point or the purpose of such a monologue. "I don't know which is more ludicrous - North Korea or me," Bruggen narrates after the fact. This is not the only evidence which suggests the director finds himself infinitely more interesting than he actually is.

Of more value here, on an emotional and intellectual level, is the presence of Jacob Nossell - a member of the absurdly inefficient theatre troupe and a young man with spastic paralysis. In a country rumoured to eugenicise its disabled, the fawning attention he gets from his tour guide is incredible to witness. Within mere hours of meeting him, she shrills that she loves him more than her own son. Jason is clearly perplexed at this insincere outburst. Later he remarks he has been treated with kindness but "I clearly sense the contempt they have for me too".

Jacob is clearly being used by the North Korean state as part of a public relations exercise and, it is clear too, that Bruggen is "exploiting the spastic" too. The Danish filmmaker admits as much in his voice-over as he gently questions his own behaviour as if having a "Eureka" moment. For such a cynical stunt as this, to address the issue with such faux-naivety is both misleading and pathetic.

Pitched somewhere between Werner Herzog, Lars Von Trier and Borat, Bruggen's film offers none of the insight or intelligence of any of these. Here, Bruggen uses a deeply upset disabled man and the hospitality of the most evil state to grace the face of the earth to make himself the star of a film. The Red Chapel highlights just how grotesque men can be, but not necessarily in the way it would like to.

No comments

Post a Comment