Louis Theroux: Savile may take its name from the two subjects who dominate this feature but, in a greater sense, this is a film which is about you and I. This is a televisual movie about the delusions we each create for ourselves, the sophisms under which we live, and the fantasies we fill our brains with each day to make our lives easier, our existence tolerable.

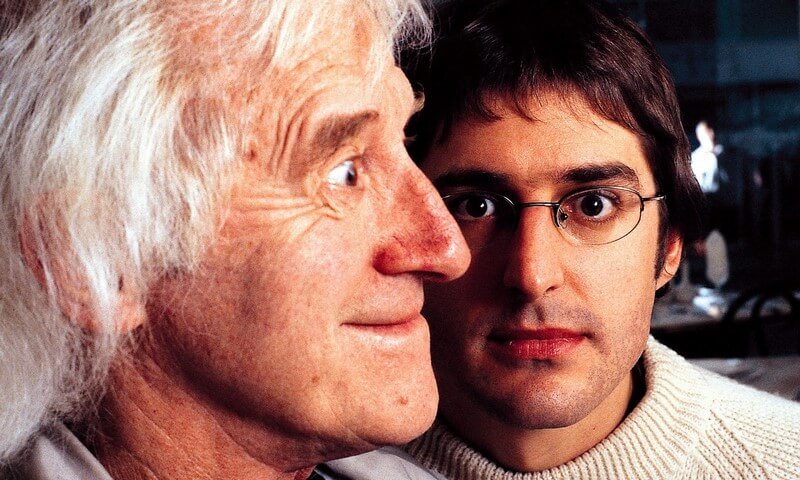

This documentary, filmed fifteen years after When Louis Met Jimmy, acts as something of a mea maxima culpa for Theroux as he looks back on his relationship with a man who, in no uncertain terms, was nothing short of a beast. As the severe nature of Savile’s crimes began to emerge after his death, the details of his child abuse, molestation and necrophilia, those around him are forced to ask themselves – how did they not know? Does their failure to notice his crimes make them guilty, complicit even?

Over the course of seventy five minutes Louis introduces us to an array of characters embroiled in the Savile story as each tries to makes sense of the evil the celebrity summoned into the world.

We hear the anguished recollections of Sam as she details the abuse suffered at the hands of Savile in church, during services. Sam is unable to detach the misery she experienced from the happier moments of the childhood; she chooses to not look back too often. To survive in the present, Sam’s mind seals off and partitions the painful past like the border of a foreign country – this is her coping mechanism. To survive daily torment, her brain does all it can to create a world in which her torment is manageable.

We too hear from Sylvia. A discreet photo of Savile adorns her dresser; she speaks of the good times she knew with the man who helped fund the Stoke Mandeville hospital she worked at. In many ways, Sylvia could be a mirror image of Sam. Whilst both try and hide from the depravity Savile inflicted upon scores of women and children, their reasons for doing so wildly differ. Sam wants to forever forget this bestial man whilst Sylvia wants to forget this man was bestial. To do so would tarnish the fond memories of the work she undertook at the spinal centre. Her brain has created a world in which all the darkness has been removed – this is the story she must tell herself to not be consumed with guilt or sorrow.

With Theroux, however, the documentarian tries his absolute best, in contrast to the two women noted above, to remember his encounters with Savile in a futile attempt at gleaning warning signs. Tapes are forensically studied - was there something he should have spotted? During the initial filming from 2001, it is shown that Savile’s mask slipped multiple times and, in a number of moments, his derogatory remarks and putrid reactions to women around him raise a flag when viewed with the benefit of hindsight. It’s easy, Theroux summarises later on, to get the answers right if you know them.

At this point, we realise, the documentary subtly points a finger at us too.

There was innuendo whilst Savile was alive - (stand-ups, for example would speculate on the DJ's life behind closed doors for unsavoury comedic material) - but not a single charge was brought against him. Posthumously, we each tell ourselves that we all knew for certain something was up and that we could, even should, have figured it out decades ago. It was a different time then and such a thing could never, ever happen again. Not now. Not in this day and age. Might this just be a fantasy too?

Is this just another story, another myth, we tell ourselves to make life more comfortable for us? The human brain has an extraordinary capacity to tell lies to itself – something which this remarkable documentary reminds us over and over.

No comments

Post a Comment