How, exactly, does one survive a nuclear war?

With a number of the world's most despotic regimes boasting access to the most powerful weapons ever realised, can we truly rest on our laurels that everything will remain safe for us here?

The government may have committed to the multi-billion pound renewal of our Trident system but what comfort would the ideology of mutually assured destruction truly grant us if a mushroom cloud were ever to blossom on our horizons?

In 2016, we're all quite confident, complacent even, that we'll never see the horrors of a Hiroshima or Nagaski again in this day and age. Even as nuclear weapons have sprouted across the world, we each sleep at night in the belief each of these warheads will remain permanently benign. What happens, though, if we're all wrong? Who is to say that Russia won't drop a couple of fat ones on us in the next couple of years just to make Jeremy Corbyn look like an ignorant fool?

Perhaps we should all embrace paranoia and start making survival plans - even an apocalyptic nuclear holocaust can be navigated with the correct preparation, right? We can't all be Tsutomu Yamaguchi , but there's no reason we can't at least try to be Robert Baden-Powell at least. With this in mind, I travelled to the Czech Republic, a former member of the Eastern bloc, to investigate how they too once planned for an inevitable Armageddon and how they aspired to survive it.

From my initial, albeit ignorant, understanding, the former Czechoslovakia did little throughout the cold war beyond erecting ugly apartments en masse, prepare for nuclear annihilation, and create an interminable amount of puppet-based morality tales. Upon arriving in Prague, my former and latter assumptions are quickly validated - the capital consists of a perculiar architectural split encompassing the eloquent designs of the medieval era and the right-angled eye-sores of the Eastern bloc years; marionette performances of Faust find their homes in a large number of these buildings.

When Francis Fukuyama declared "the end of history", his belief that capitalism had truly vanquished communism, he may well have used Wenceslas Square to illustrate his point. Where future leaders once delivered revolutionary speeches to huddled masses of Czech citizens, a perfunctory iteration of a Marks and Spencers outlet now stands. Where Soviet tanks had once rolled, occupying the nation's citizens with their military might, Coca-Cola parasols now sway.

Yet, locked away under this hyper-modern bricolage of a modern European city, remains one of the last true surviving remnants of the Cold War-era - a science fiction dream made real. Underground concrete corridors stretch out like treeless roots; the might oak from which they had stemmed long since cut down by a Velvet Revolution . Here lies a true-to-life, actual nuclear bunker which, I learn, would still be called into operation were an unlikely attack ever take place on this beautiful city. Should Britain, I wonder, invest in one of these too in case an Armageddon comes to our green and pleasant lands?

Constructed in the 1950s, Prague's bunker, when I visit, can be considered an out-dated peculiarity at best, an ill-fated piece of propaganda more fittingly. Built in parallel to the hundred foot high statue of Joseph Stalin (which was torn down seven years later when even the communists realised he was something of a bad egg), the woeful project now feels like a woeful and eccentric project aimed at disproving the myth of the efficacy of central, public planning.

Mike, my friendly tour guide, explains a number of the bunker's many foibles with whimsy and joviality.

The first issue, and an important one, relates to space. Our imaginations may, when presented with the word "bunker", conjure images of grand halls, of dormitories, of kitchens preparing meals for the thousands of refuge-seekers inhabiting the bunker whilst nuclear war rages overhead. The truth is something much more humdrum.

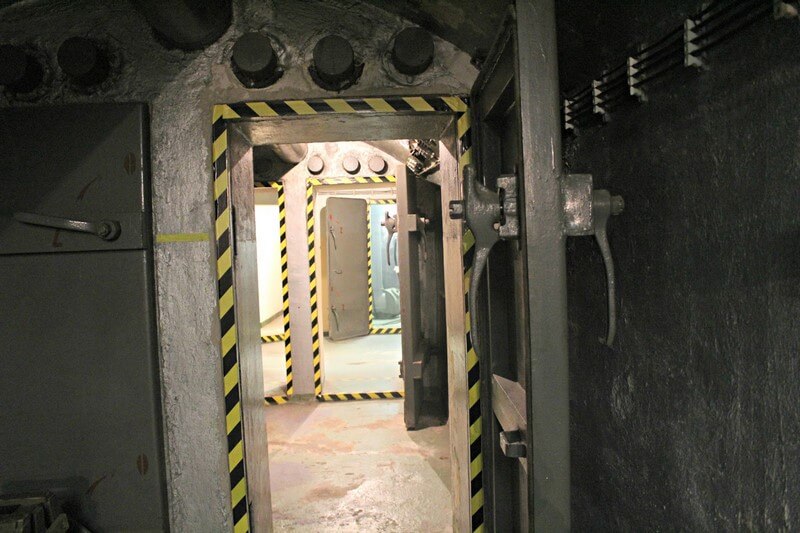

As the monstrous steel door at the facility's entrance slams behind me, sealing this writer off from the outside world, a flight of stone stairs spirals down to a series of labyrinthine corridors which, fascinatingly, lead simply to one more spindly, ricketty and stone cold corridor. Surely, I ask, there must be more to this hide-away than these austere surrounding? Where else could the 5'000 inhabitants (the official capacity of their bunker) be able to live, sleep and regroup until it becomes safe to once more return to the earth's surface?

The design, I learn, is indeed truly poorly thought out. Each person who stays here is allocated only two square meters of space each to stand, sleep and converse in - this area must also provide storage room for their backpack (which should be full of enough supplies for four weeks. Each bunker-dweller must bring these supplies with them too). So, to avoid immediate death in the shadow of man's most evil invention, Czech citizens were invited to slowly starve, rot and suffocate in overly crowded and barren tunnels instead.

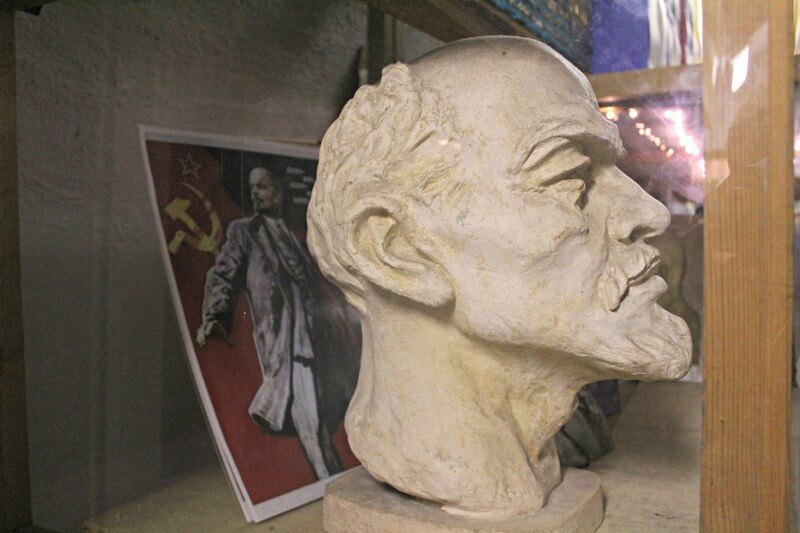

The depressing visions of wall-to-wall corpses lining these corridors quickly fades from my mind as the tour presents me with the opportunity to dress up in the military regalia of the Czechoslovakian army of five decades ago. I feel pangs of something close to pride, albeit fettered with a smattering of guilt, as I hold a replica rifle in front of a hammer and sickle flag - is this, I wonder, a sensation close to how Zimbardo's subjects once felt?

At this point, too, I learnt of perhaps the greatest failing in the bunker's design. The walls are regularly breached by rain and, as such, would do a poor job of keeping out radiation. Yet, perhaps ludicrously, it has been the job of the same caretaker for the last thirty five years to maintain the integrity of this non-operational bunker just in case the unthinkable did indeed happen. If so, the citizens of Prague would fight it out to enter a bunker which would provide no relief from nuclear poisoning, whilst also subjecting its proprietors to starvation and crushing. The caretaker's job may, given this knowledge and location, have recalled Kafka to mind for many but perhaps the most obvious point of reference for this gentleman's story may come in the form of Sisyphus.

As I leave the bunker, its not hard to come to the conclusion that the facility was initially envisioned as an ill-judged piece of communist propaganda and no more. Now, nearly three decades after Fukuyama suggested history pulled its final curtain, the same location remains in tact solely to feed capitalism; the nation's communist history is regurgitated and presented to the many tourists who visit, to be consumed over and over. A communist past has become a capitalist selling point.

My visit to the bunker, to see if there was any point in Britain investing in one, is conclusive. Were the black light and white heat of nuclear power to envelope the country, there would be no escape. No concrete corridor, weather-proof or otherwise, could save us. What good would Trident, or any other nuclear weapon be, if we were all ablaze in agony, fallout rotting our bones?

|

| A nuclear family |

The crushing realisation dawned on me - Britain's nuclear weapons fulfill exactly the same purpose as Prague's nuclear bunker. They exist solely as useless propaganda machines, draining the state's economy and committing huge swathes of our money which could be spent usefully elsewhere.

It may be easy to laugh at a shelter which provides no such thing, but the British sit on a multi-billion pound deterrent which is nothing more than an illusion. Our safety is nothing more than a story we tell ourselves in an infinite and infinitely chaotic universe. Perhaps all we can do is stop worrying, though I doubt any of us could ever bring ourselves to truly love the bomb.

No comments

Post a Comment